In the rainy pre-dawn hours of June 25, 1950, North Korean tanks crossed the 38th parallel to invade the South.

Seven hours later the Communist forces issued an official declaration of war.

The provocation was the most serious test to date for the nascent United Nations. Eager to prevent another World War, the Security Council quickly condemned the invasion.

Two days later, UNSC Resolution 83 urged member states to repel the North by force in order to restore international peace.

Over three bloody years, a remarkable cadre of 16 nations—the United States, United Kingdom, Ethiopia, Colombia and Thailand, among others—sent troops to South Korea’s aid.

The unprecedented international support demonstrated that the Korean War wasn’t only Korea’s war.

In remarks delivered at a Memorial Day ceremony last month, General Walter Sharp, Commander of United States Forces Korea and the United Nations Command, said, “It was here that forces from the Republic of Korea, the United States and the United Nations proved to the world that we would not stand idly by while a peaceful nation was invaded by an aggressor.”

A Day of Remembrance

An estimated three million soldiers and civilians died during of the conflict, with the bulk of the terrible toll borne by Koreans themselves.

Nevertheless, just a few years into what would become an historic recovery, a devastated nation remembered its fallen heroes. On June 6, 1956, Hyeonchung-il (현충일), or Memorial Day, became an official holiday.

Since the month of June includes both Memorial Day and the anniversary of North Korea’s invasion, it’s when Koreans honor national defense.

Students place thousands of flags and chrysanthemums on soldiers’ graves, and on Memorial Day itself, flags fly at half-mast and at 10-o’clock, a one-minute siren sounds across the nation.

Of course, the holiday isn’t unique to South Korea. Many countries have established days to honor their war dead since freed slaves founded the holiday in 1865 at the end of the American Civil War.

In Commonwealth nations, Remembrance Day honors fallen soldiers, while in the Philippines, it’s Bataan Day and in the Netherlands, Dodenherdenking, or “Remembrance of the Dead.”

The fact that nationals of these countries also died on South Korea’s behalf is why June 6th also honors them.

Blood Ties

Last year marked the 60th anniversary of the start of the Korean War, and across the country it was easy to find evidence of a nation’s gratitude.

Seoul subway cars were lined with posters saying “thank you” in Spanish or Turkish. As part of official commemorations, the South Korean government invited elderly veterans back to see the remarkable prosperity they helped create.

Peter Machielse’s grandfather is among those vets. Growing up in the Netherlands, Peter listened to his grandfather’s war stories, tales that piqued his interest in Korea, and led him here last year to attend a youth peace camp.

After writing about his experience in a Dutch veteran’s magazine, the 26-year-old was selected by the Korean War Memorial Foundation to receive a scholarship.

Established in 2010, the foundation provides educational scholarships to the descendents of overseas vets. Board member Ernst Lee says that Koreans must not forget the sacrifices made by foreign troops.

When Peter is asked if he feels any pride for what his grandfather did some 60 years ago, he nods. “War is not always a good option, but the result is the freedom and prosperity that [South] Korea has at the moment. When I’m walking in Seoul and see all the lights and wealth, I think maybe if the U.N. forces didn’t support Korea, it wouldn’t be here [today].”

Remembering the “Forgotten War”

Despite the passage of time and its overseas reputation as “The Forgotten War,” there are many sites to help visitors learn about the war’s origins and legacy.

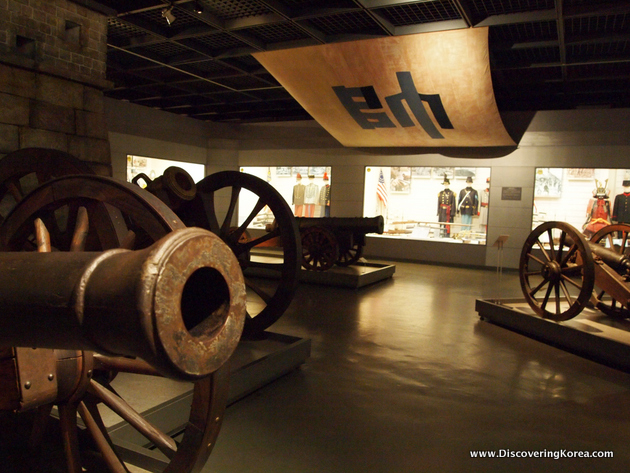

Among them, the War Memorial of Korea (전쟁기념관) in Seoul is the most comprehensive. Opened in 1994, the museum displays over 13,000 items on six floors of galleries.

Although the bulk of the collection chronicles the Korean War, excellent exhibits chronicle centuries of conflict against Mongol, Chinese, Japanese and French invaders.

Outside, over 100 mothballed fighter jets, tanks and artillery batteries from more recent battles are displayed. But the memorial’s most poignant piece is the Statue of Brothers.

The 18-by-11-meter sculpture depicts two brothers—one fighting for the South and one for the North—who meet in a battlefield. Their embrace expresses love, reconciliation and forgiveness.

Another Korean War footprint is located just south of the Hangang (River). Seoul National Cemetery (현충원) is 353 immaculately-maintained acres that hold the remains of nearly 168,000 fallen soldiers, independence activists, police and three former presidents.

The site of the president’s annual Memorial Day address, over 200,000 people are expected to visit the cemetery on June 6th.

The most popular war monument of them all is the DMZ. The so-called “demilitarized zone” is a 4-kilometer-wide belt that separates the two Koreas.

Despite its dubious distinction as the world’s most heavily-militarized border, the DMZ attracts millions of tourists each year who are curious to see this Cold War anachronism for themselves.

Visitors can descend into invasion tunnels bored by North Korean soldiers, peer into the reclusive country via telescope, or trek along recently-opened nature trails. The de facto ecological preserve is an unexpected benefit of the six-decade-long stalemate.

Entering the Military Armistice Commission conference building in the truce village of Panmunjeom (판문점) is a DMZ highlight and something worthy of any traveler’s “bucket list.”

Once inside, the tension is palpable as unsmiling North Korean guards peer inside and South Korean soldiers in dark aviator shades stand silently with fists clenched in a Taekwondo pose.

Since the bright blue building straddles the actual border, visitors can step foot into North Korea—if only for a moment.

An Ongoing Threat

Sadly, the war that devastated the Korean peninsula hasn’t ended. On July 27, 1953, an armistice was signed in lieu of a peace treaty and 58 years later the two sides remain on the brink of war.

Just last year, 51 South Koreans were killed when the North torpedoed the Cheonan naval corvette and showered the residents of Yeonpyeong Island with artillery shells.

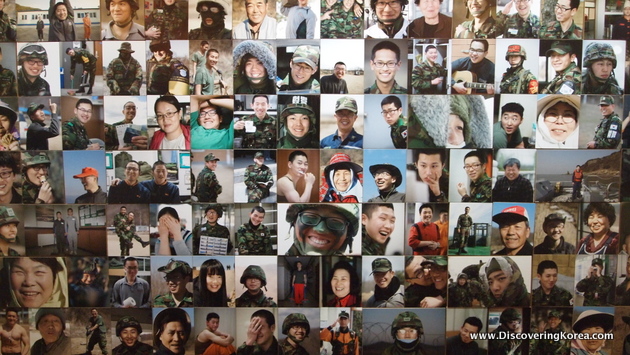

Many of the dead were the nation’s citizen-soldiers, since, with few exceptions, all South Korean men must serve two years of military service. Although conscription is acknowledged as a rite of passage and a social equalizer, it’s also dangerous.

Last April, as the nation mourned the young sailors who perished aboard the Cheonan, there was something particularly heartbreaking about the soft faces that stared back from the official portraits.

This June 6th, as the peonies and dogwoods bloom across Korea, the nation will mark its 56th Memorial Day. On this day, ordinary citizens are reminded of the ongoing efforts to recover and identify the remains of fallen soldiers—4,000 of whom have been discovered since 2000 alone.

Also on June 6th, South Koreans will take a moment to consider the nation’s soldiers who are engaged in overseas peacekeeping efforts in Lebanon or in anti-piracy missions in waters off Somalia.

Perhaps most of all, those of us living in South Korea should acknowledge the thousands of Korean and U.N. forces that protect us every day on the country’s front lines.

For Your Information…

| Open: | War Memorial: 09:00-18:00 (until 19:00 Sun. & holidays, until 21:00 Wed. & Sat.), Closed Mondays. Ntl. Cemetery: 06:00-18:00 (Mar.-Oct.), 07:00-17:00 (Nov.-Feb.) |

| Admission Price: | War Memorial: ₩3,000 for adults, ₩2,000 for studentsNtl. Cemetery: Free Admission |

| Address: | War Memorial: Seoul, Yongsan-gu Yongsan-dong 1(il)-gaNtl. Cemetery: Seoul, Dongjak-gu Dongjak-dong San 44-7 |

| Directions: | War Memorial: Samgakji Station (#428/#628) on Lines $ & 6, Exit 12. Ntl. Cemetery: Dongjak Station (#431/#920) on Lines 4 & 9, Exit 8 |

| Phone: | War Memorial: 02-709-3139Ntl. Cemetery: 02-815-0625 |

| Website: | War Memorial Site National Cemetery Site |

About Matt Kelley

Matt Kelly is native of the US Pacific Northwest and is half-Korean by ethnicity. He lived in Korea for five years and has written hundreds of travel guides for Wallpaper, TimeOut, the Boston Globe and Seoul Magazine and was a host for several different variety shows on Korean radio and television.