The House of Sharing in Korea is a special place located about 45-minutes southeast of Seoul in Gyeonggi Province.

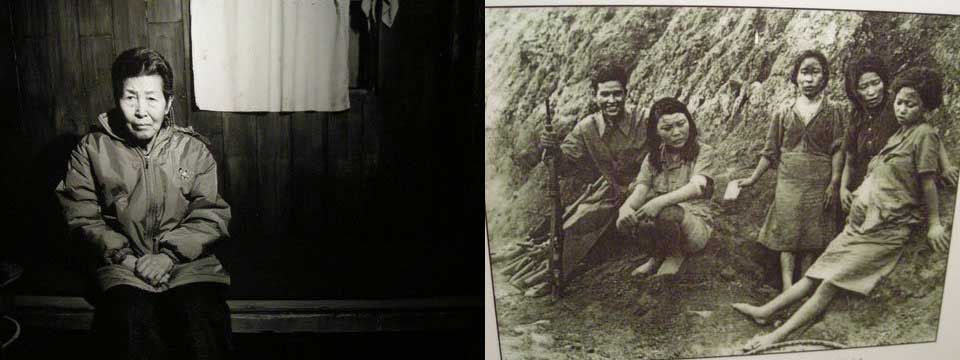

Built in 1995, the house is home to seven elderly Korean women in their 70s and 80s. The house and the halmonis (할머니), or grandmothers, who live there have painful stories to tell. During World War II, they were forced by the Japanese military to become “comfort women,” or sex slaves.

Their fate was shared by some 200,000 girls and young women from all across Asia.

The largest number of these girls and women were Korean. After being coerced or kidnapped to serve the Japanese military’s soldiers, they endured systematic rape and venereal disease. Many emerged from the war alone and impoverished, traumatized by their experiences and physically unable to have children.

Even after the War, however, feelings of shame and abandonment by their families compelled most of Korea’s former sex slaves to keep their torture a secret, even to this day.

But in 1991, Kim Hak-soon became the first halmoni to publicly testify her experience as a sexual slave. Her courageous coming out helped expose the ongoing suffering of the halmonis, and helped spark an international movement to demand a formal apology from the Japanese government.

A member of my own extended family, Jan Ruff O’Hearn, is an outspoken, former Dutch-Indonesian “comfort woman.”

Thanks to their efforts, in 1992, a home in central Seoul was established to care for a handful of these frequently-ill, elderly women.

In 1995, the House of Sharing was built on a quiet piece of land donated by Korea’s Joggye Buddhist Order located on the outskirts of Gwangju, in Gyeonggi Province. In addition to living quarters for the halmonis, the House of Sharing includes a lecture hall, an outdoor entertainment stage, and the Museum of Sexual Slavery by the Japanese Military.

The museum, which was built in 1998, includes wartime photographs, art by the halmonis, and a life-size, so-called “comfort station” cubicle. Outside the door are rows of wood blocks with the Japanese names given to the sex slaves. If a woman was unavailable, due to venereal disease, her block was turned over.

Despite irrefutable documentary evidence proving the Japanese government’s role, as recently as March of 2007, then Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe caused an international uproar when he suggested that the women were willing prostitutes.

The ensuing furor helped encourage passage of the United States House of Representatives Resolution 121, which asked the Japanese government to formally apologize and to teach Japanese students about their country’s past crimes.

The resolution was introduced by Representative Mike Honda, himself an American of Japanese heritage.

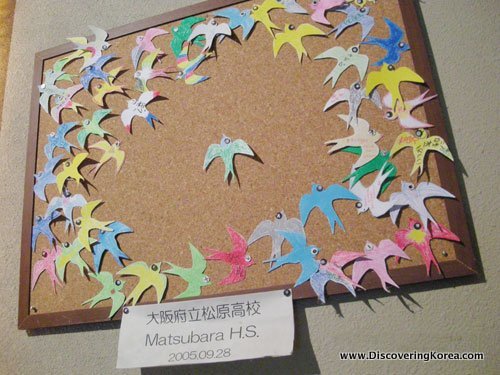

Rep. Honda of the U.S. isn’t the only person of Japanese descent who cares about the halmoni. For me, the most touching part of the House’s museum is an alcove full of posters, paper flowers and gifts, most of which are from Japanese school children.

And furthermore, the House was built, thanks to funding from the Korean government, as well as from Korean and Japanese individuals. It’s just more evidence of the power of person-to-person relationships, even if governments refuse to accept responsibility.

When I first visited the House of Sharing, we watched a tape of one halmoni’s testimony. Although quite small and shy, she had a powerful presence, even via a television screen.

Sadly, upon checking the House’s Web site, I learned that she’s likely passed away. As one might imagine, visiting the House of Sharing is an emotional experience. Korean, English and Japanese language tours are available.

The English tours usually occur about once a month, and groups meet in Seoul for the bus and taxi trip necessary to get there. Once there, if you’re really lucky, one of the halmonis will sit with your group and share her story.

But, due to their advanced age and failing health, a videotaped testimony is more likely. Sadly, time is running out for these courageous survivors.

Finally, if you’re in Seoul, every Wednesday, several halmoni and their supporters conduct weekly protests outside of the Japanese embassy to demand a formal apology and redress.

In 2012, the grandmothers marked their 1,000th consecutive demonstration. It’s a remarkable testament to their strength and courage.

For your information…

| Open: | 10:00-17:00 (Closed Mondays) Wednesday protests outside the Japanese embassy in Seoul take place at 12:00. |

| Admission Price: | Museum Admission: Adults: 5,000 won, Students: 3,000 won |

| Address: | Gyeonggi Province, Gwangju-si, Twoichon-myeon, Wongdang-ri 65 |

| Directions: | Take Seoul Metro Line 2 to Gangbyeon Station and walk to Technomart bus stop. Take bus #1110-1 to Gwangju City Hall. From there, take a taxi to Nanumae-jip. |

| Phone: | 031-768-0064 |

| Website: | English |

About Matt Kelley

Matt Kelly is native of the US Pacific Northwest and is half-Korean by ethnicity. He lived in Korea for five years and has written hundreds of travel guides for Wallpaper, TimeOut, the Boston Globe and Seoul Magazine and was a host for several different variety shows on Korean radio and television.