Sometimes it takes your breath away how fast and how completely Seoul changes. Indeed, it can feel like the city is always changing. In what feels like just weeks an old neighborhood is razed and huge new apartment towers stand in its place.

This dynamism is part of the city’s excitement and how Korea successfully emerged from the ravages of war. But in this relentless push forward, too many of Seoul’s most historic areas are being destroyed.

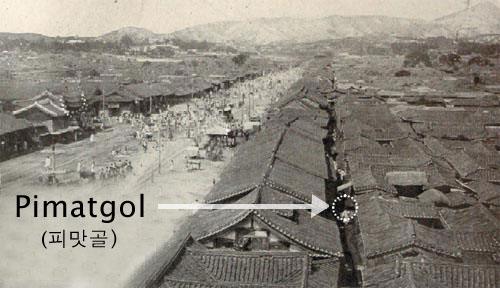

One particular example is Pimatgol (피맛골), a historic street located in the central Jongno-gu district.

The Chinese characters of Pimatgol literally mean “avoid horse alley,” which was the why this narrow passage, just three meters wide in most places, was created some 600 years ago during the Joseon Dynasty.

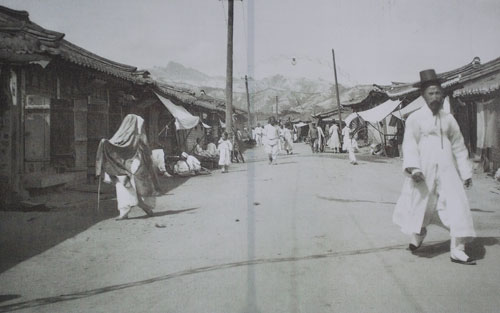

Then even more than now, Jongno was the main thoroughfare connecting the city, and the frequent passage of aristocrats, called yangban (양반), on horses or in sedan chairs created an inconvenience for the common people, who were required to stop and prostrate themselves as they passed.

To avoid this formality, Pimatgol, a 2.5-kilometer side alley was created to allow Seoul’s working people quick passage. Bars and eateries sprang up in kind.

The result was a cramped and colorful sliver of Seoul life. In recent decades, it wasn’t horse-drawn dignitaries that people avoided. But when student democracy activists slipped into the alley to avoid police crackdowns, restaurant owners gave them shelter.

But today, Pimatgol’s primary attraction is the scores of restaurants. Some have existed for 70 years or more, serving unpretentious plates of grilled mackerel, a delicious mug bean, pork and vegetable pancake called bindaetteok (빈대떡), and the pork rib and potato soup called gamjatang (감자탕).

And of course, everything tastes better with the sweet Korean rice beer, makgeolli (막걸리). In the evening, the flashing lights and steady foot traffic makes the alleys feel even narrower.

But these alleys are quickly becoming relegated to Seoul’s past. In the 1980s the area was marked for “urban renewal,” and a big bank and the iconic Samsung Securities Tower created impressive barriers along Pimatgol’s path.

In 2004, a six-month protest by shopkeepers wasn’t successful in preventing another block from being razed and replaced. A few restaurants made new homes in the uninspired “Jongno Town” tower. But customers complain that the food just doesn’t taste the same, and I’m not surprised.

A slow decline followed until May 2009, when the half-block immediately behind the Kyobo Tower, considered the most picturesque and best preserved part of the alley, was demolished. Basically, the entire section from Kyobo to Jonggak Station is now gone.

It’s true that what remains of Pimatgol is mostly dirty and uncharmed. But it’s a shame that efforts weren’t made to preserve this historically significant slice of seongmin (성민), or working-class life from old Seoul.

I understand Korea’s insatiable desire to tear down the old to build gleaming towers of steel and glass… after all, the country should be proud of its improbable rise from the destruction of war. But why not spend a fraction of this new-found wealth on preserving one-of-a-kind places like Pimatgol?

Today, everything in the Jongno area feels huge. Both Jongno and Gwanghwamun are among the city’s widest thoroughfares, and high rises flank each side.

Small, derelict shops along a narrow alleyway seem out of place. But a mix of old and new, different sizes and shapes helps residents and travelers alike to feel an intimacy with a city – something that a uniform grid of business towers simply can’t do.

If you want to see a piece of Pimatgol before it’s all gone, you’d better hurry. Of what’s left, the best place is actually across the street between Jongmyo Royal Shrine (종묘) and Tapgol Park (탑골공원). Take a seat, eat a meal, and wander down one of Seoul’s most historic and endangered trails.

About Matt Kelley

Matt Kelly is native of the US Pacific Northwest and is half-Korean by ethnicity. He lived in Korea for five years and has written hundreds of travel guides for Wallpaper, TimeOut, the Boston Globe and Seoul Magazine and was a host for several different variety shows on Korean radio and television.