In the northern Seoul neighborhood of Hongji-dong (홍지동) is a stately Western-style home that’s located right next to part of Seoul Fortress (서울성곽).

Built in 2004, the house features a stone exterior with wood pillars painted to resemble aged copper. Four years ago, the former residence became the Musée Shuim (쉼박물관), and is now home to the world’s largest collection of Korean funerary folk art.

The Musee Shuim’s name is a play on the Korean word for “rest,” meaning both a short break as well as eternal sleep.

Musee Shuim was created after the death of the founder’s husband, whose passing inspired her exploration of Korea’s colorful folk art that associates birds, dragons, phoenixes and dokkaebi, a sort of Korean goblin, with death.

Inside the museum, over 1,000 pieces are displayed amongst the trappings of an upper class home – so sitting atop dark wood floors and beside sumptuous drapes are display boxes that contain wooden figurines, and cranes with flappable wings hang from the ceiling next to pink crystal chandeliers.

Somehow, they complement each other nicely!

In addition to the folk art pieces, however, Musee Shuim’s collection includes other items related to death rituals. For example, jegi, or the dishes used in religious services for ancestors are on display.

These dishes, frequently made of white porcelain, were used to carry food, alcohol, incense and candles for official services. Frequently these items were buried with the deceased since it was assumed they would enjoy similar items and activities in the afterlife.

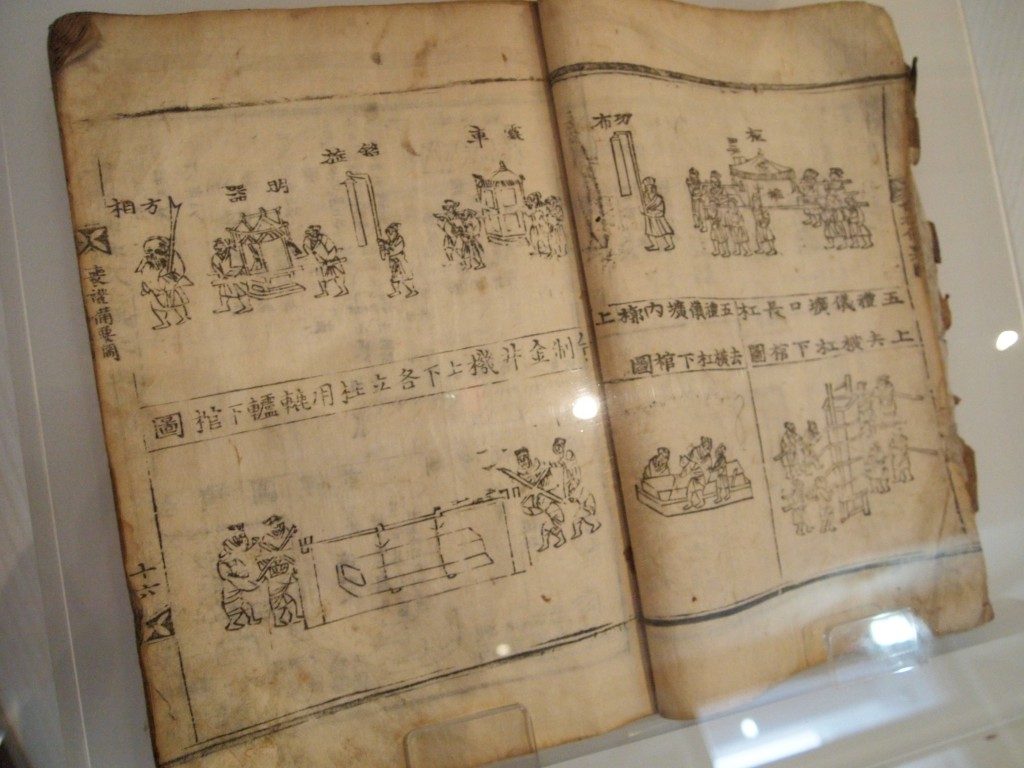

Another part of the collection is a 1782 edition of the Sangrye Biyo, a book of prayers and protocol for funeral rites during the Joseon Dynasty.

Without a doubt, the Musee Shuim’s prize piece is a fantastic funeral bier or sangyeo.

Resembling an ornate palanquin, the sangyeo was used by upper class families to carry the deceased to the funeral site. The Musee Shuim’s funeral bier came from Jinju, in South Gyeongsang Province.

Created in the shape of a house, it’s decorated with painted flowers, dragons, dokkaebi, hanging lanterns, decorative tassels and even shovels.

Attached to the front and rear of the bier is a Yongsupan, or dragon-shaped board. Intended to protect the soul and drive away evil spirits, the dragon was considered a symbol of authority and safety.

Every depiction plays a role in leading the deceased into the other world.

In an art industry that can often seem inaccessible, there’s nothing pretentious about Korea’s folk art traditions, and whose maker is usually a mystery.

Furthermore, despite what’s by definition morbid, the colorful wooden figurines and plaques are meant to depict happiness and joy rather than the tragedy of death.

While it’s sad that these items are rarely used anymore, it’s a fascinating look into Korean traditional culture, and one that the public can enjoy at Musee Shuim.

For Your Information

| Open: | Summer: 10:00-18:00 (Mon-Sat), 14:00-19:00 (Sun); Winter: 10:00-17:00 (Mon-Sat), 14:00-19:00 (Sun) |

| Admission Price: | ₩7,000 |

| Address: | Seoul Jongno-gu Hongji-dong 36-20 |

| Directions: | Hongje Station (#324) on Line 3, Exit 1 |

| Phone: | 02-396-9277, 010-2589-5890 |

| Website: | Official Site |

About Matt Kelley

Matt Kelly is native of the US Pacific Northwest and is half-Korean by ethnicity. He lived in Korea for five years and has written hundreds of travel guides for Wallpaper, TimeOut, the Boston Globe and Seoul Magazine and was a host for several different variety shows on Korean radio and television.