During the Joseon Dynasty, Seoul had both a north village and a south village.

While the south village was home to lower ranking officials, the north village, called Bukchon (북촌), was built between Gyeongbukgung (경복궁) and Changdeokgung (창덕궁) palaces, and was historically home to high ranking palace officials.

The palaces were built on what was considered Seoul’s two best plots.

According to Korean baesanimsu (배산임수) principles, which are similar to feng shui, their location is auspicious since it sits on the slopes of a mountain with water – the Hangang river (한궁) and Cheonggyecheon stream (청계천) – in front.

Situated in-between, Bukchon also enjoyed the area’s positive yang energy.

Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village is the city’s last neighborhood with a high concentration of traditional homes, called hanok (한옥).

Just 30 years ago, there were over 800,000 hanoks in Seoul, but today only some 12,000 remain with 900 concentrated in Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village.

Hanok are typically single-story structures made of clay, wood and stone with ondol heated floors topped by curved tile roofs called giwa (기와).

In this part of Korea, they usually take the shape of the Korean letter “geok” (ㄱ) or “deegut” (ㄷ), which create a nice central courtyard. In the cold north they are often square shaped to help retain heat, while the warmer southern region’s hanok can have an open “I” shape.

Today there are about 2,300 homes in Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village, but back in the day there were probably no more than 30 villas here.

But when Japanese annexation ended the Joseon Dynasty in 1910, social and economic forces conspired to divvy up the old villas into hundreds of compact lots.

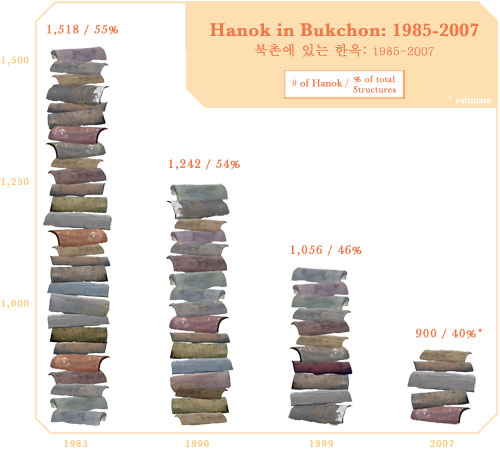

Unfortunately, what remains is only about 40% hanok and very few of them date from the Joseon period.

Most were mass-produced in the 1930s, and space restrictions required shorter roof eaves and the average hanok in Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village is only about 25 pyeong in size (about 83 sq. meters or 900 sq. feet), although there’s one 150-pyeong monster hanok.

Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village hasn’t escaped a government policy to tear down hanok, or the desire of many Koreans to abandon traditional housing for the sea of ubiquitous apartment tower blocks that started ravaging Seoul’s skyline in 1962.

In fact, it’s only recently that Seoul’s tourism officials realized the value of Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village and moved to protect it. Unfortunately, their preservation plans have been plagued with snafus.

While the neighborhood has been better preserved than most, it’s nearly impossible to find a view that’s uninterrupted by ugly, multi-story brick homes.

By 2000 there were just two streets in the Gahoe-dong neighborhood that were filled entirely by hanok.

In 2001, the Seoul Metropolitan Government launched its “Bukchon Project” (in English here and Korean here), investing 84-billion won to encourage residents to register and renovate hanok via grants and low-interest loans.

The city undertook a detailed architectural survey and worked to improve roads, street lighting and tourist signage while changing zoning laws and imposing new height and design restrictions.

Although 200 neighborhood hanok were renovated by 2007, many others were demolished.

While the number of hanok in Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village continues to fall, there’s also new hanok construction happening.

Living in a hanok is becoming fashionable, and the city is working hard to promote Bukchon as a top tourist destination. The rise of wine bars and art galleries in trendy, next-door Samcheong-dong also brings a lot of foot traffic.

If you pick up a neighborhood map at the Bukchon Cultural Center, you can also purchase the new “Bukchon Museum Freedom Pass.”

For 10,000-won, you get access to five museums: the Gahoe Museum, Hansangsu Embroidery Museum, Dong-lim Museum, Museum of Korean Buddhist Art, and my personal favorite, the Seoul Museum of Chicken Art.

As hanok continue to be demolished in other parts of Seoul, at least one neighborhood is making an effort to preserve them.

Let’s hope the sea of arching tile roofs and winding alley roads still found in Seoul Bukchon Hanok Village can stick around.

For Your Information…

| Open: | 24 hours |

| Admission Price: | Free |

| Address: | N/A |

| Directions: | Anguk Station (#328) on Line 3, Exit 2 |

| Phone: | 02-3707-8270 |

| Website: | Official Site |

About Matt Kelley

Matt Kelly is native of the US Pacific Northwest and is half-Korean by ethnicity. He lived in Korea for five years and has written hundreds of travel guides for Wallpaper, TimeOut, the Boston Globe and Seoul Magazine and was a host for several different variety shows on Korean radio and television.