If you believe the ads in the windows of Seoul real estate offices, an urban mega-project resembling Dubai and a green space to rival New York’s Central Park are both coming to Seoul’s Yongsan District (용산구).

According to the plan, American architect Daniel Libeskind’s “Dream Hub IBD” will transform 56 hectares of prime riverfront real estate into an arch of towers inspired by a Silla Dynasty crown.

Next door, a massive park will create a green oasis in the heart of the city.

Combined, the projects suggest that Yongsan could eclipse Gangnam as the city’s most desirable district.

Foreign Bootprints

Realizing this ambitious vision would require the relocation of the United States’ Army Garrison Yongsan.

The Americans have occupied the 2.5 square kilometer area since Japan’s defeat in World War II. Previously, it was the Imperial Japanese Army that claimed the strategic area between downtown Seoul and the Hangang river.

In fact, as far back as the 13th century, Mongol invaders, and then Chinese ones, based their forces in the area called “Dragon Mountain.”

Plans to relocate the American base were pushed back to 2019. If that happens, Yongsan’s quirky character is sure to radically transform. But in the meantime, the district remains home to Seoul’s most multicultural neighborhoods.

Attractive hamlets like Haebangchon (해방촌), Gyeongnidan (경리단) and Ichon-dong (이촌동) offer an uncommon experience in Korea―streets and restaurants where faces and languages other than Korean predominate.

Seoul’s Western Concession

Outside Noksapyeong Station’s Exit 2 is an attractive, tree-lined sidewalk. A few hundred meters down the brick path is Yongsan Garrison’s “Friendship Gate.”

Guarded by U.S. troops and barbed wire, it’s also the crossroads of two expatriate enclaves. Pass the gate and a wall of traditional Korean pots to reach Yongsan 2-dong, better known as Haebangchon.

Or cross the busy intersection and hang a left up Gyeongnidan―local parlance for Hoenamu Street (회나무길).

If the charcoal barbecues stored on the patios don’t give it away, the occasional Canadian flag or tanning advertisement might: Haebangchon and Gyeongnidan are favored neighborhoods of so-called “Western” expats.

Aside from realtors advertising themselves as “USFK-approved” and the occasional group of men jogging in gray and green army sweats, there isn’t a conspicuous military presence off base.

But should you seek it out, the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) outpost Canteen is open daily. As the small brass donation plaques on every piece of furniture suggest, the basement bar is an insider’s haunt.

Like much of Seoul, Haebangchon is gentrifying. Stylish cafés, restaurants, bars and boutiques are replacing modest storefronts and places like Canteen.

Above the VFW outpost is H (ㅎ), a stylish pub specializing in Korea’s favorite creamy rice wine, makgeolli (막걸리). The menu is organized by region, so under the Chungcheong Provinces, for example, is Boryeong’s Misan varietal.

The wine, described as thick and seven percent alcohol, paired nicely with short ribs and a platter of potato pancakes.

Over in Gyeongnidan, the upscale transformation is occurring even faster. As the narrow road winds up the mountain, the neighborhood’s hybrid culture takes quirky turns.

For example, beside the Algerian embassy is Café EJ, an attractive spot with an identity crisis. Is it a café or a gift shop? Is the theme post-Impressionist Paris or 1950s Americana?

Bottom line: where else can you find Toulouse-Lautrec prints and rows of vintage “Blush Becomes Her” and “Midnight Mischief” Barbies in their original packaging?

(Very) Little Tokyo

South of the Yongsan Garrison is the very different expat enclave of Ichon-dong. Sometimes called “Little Tokyo” for its Japanese community, the residential area along the Hangang features quiet side streets and petunia baskets hanging along the main thoroughfare.

Although it’s not uncommon to hear passers-by speaking Japanese, the community’s presence is most felt with a handful of restaurants and businesses concentrated east of Sachon 7-gil (사촌7길).

Among them, Bocheon (보천) is famous for its udong hot noodle soup and deopbap, while the wood-paneled Sanuki (사누끼) serves excellent tonkkaseu breaded cutlet and memil noodles.

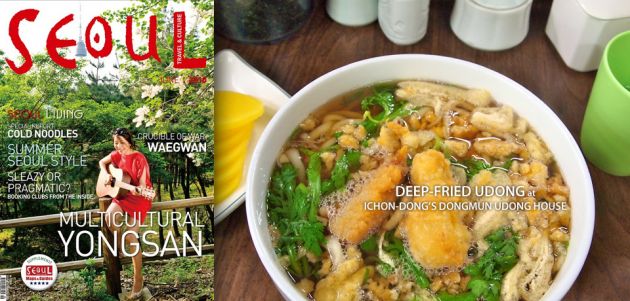

Another neighborhood favorite is Dongmun Udong House (동문우동전문점). The spot’s retro sign confirms its iconic status as a purveyor of udong, naengmyeon and knife-cut noodles.

The place is popular with suits and housewives alike, so table space can be hard to get. But sitting at the counter allows for hand-to-hand exchange of the bowl of hot noodles.

The Deep-Fried Udong (5,000 won) includes two deep-fried prawns atop thick wheat flour noodles, slices of aburaage fried tofu, and scallions in a sweet soy broth, punctuated with bits of batter that stay crunchy until the very end.

For the home cook, the walls of the tiny Mono Mart (모노마트) are neatly (and completely) covered in imported Japanese foodstuffs, while chain stores offer unique treats at their Ichon-dong stores, such as Paris Baguette’s okkosomiyakki.

Namsan’s Parks

Yongsan has long endured foreign invaders, so it’s fitting that the district also pays tribute to Korea’s patriots.

Among the most revered is the Korean independence activist and pan-Asianist Ahn Jung-geun (안중근), who is memorialized in Namsan Park’s far western section. In 1909, with Korea on the verge of annexation by Japan, Ahn assassinated Japan’s Resident-General of Korea, Ito Hirobumi, in Harbin, China.

For this act, he, too, was killed. A large memorial stele and hall erected in Ahn’s honor are located alongside a popular fountain, a public library and park offices.

Namsan Park’s south end is another attractive destination. As part of an ambitious project to rehabilitate the mountain, apartments were demolished in 1994 to make way for an Namsan Botanical Garden (남산야외식물원).

Over 100,000 plants and an exhibition hall describing the historical, cultural and natural importance of the mountain park were installed.

On offer year-round and free to the public, guided group tours of the park are available by appointment.

Century 21

The perennially tenuous political situation on the Korean Peninsula means it is very possible the U.S. military won’t leave Yongsan in 2019 as planned.

Although there are plenty of real estate speculators eager for a confirmed move-out date, it’s easy to imagine that many current residents are wary of what change will come.

Nevertheless, it appears that centuries of foreign military presence there are slowly coming to an end.

And sooner or later, Yongsan, long coveted for its strategic military location, may be the target of a new invasion―a wholly civilian one.

This article appeared in the June 2010 edition of SEOUL magazine, published by Seoul Selection.

About Matt Kelley

Matt Kelly is native of the US Pacific Northwest and is half-Korean by ethnicity. He lived in Korea for five years and has written hundreds of travel guides for Wallpaper, TimeOut, the Boston Globe and Seoul Magazine and was a host for several different variety shows on Korean radio and television.